Debridement of chronic wounds – a key step in preventing and managing wound infections

Chronic wounds cause pain and misery to millions of people around the world. Removing slough and biofilm through... read more

Wound cleansing and the application of adequate phase-oriented wound dressings are an important line of defence against surgical site infections (SSI), a serious complication which affects millions of patients every year. Dressings not only act as a physical barrier to avoid wound contamination but can actively support the healing process.

It is hard to find something more vital to mankind than healing and dressing a wound – a medical art that dates back to ancient times: In one of the oldest medical texts, a clay tablet dating back to 2200 BC, wound dressing – “making the plasters” – is described as one of the “three healing gestures,” together with washing wounds and bandaging them1. Our ancestors used mixtures of mud or clay, plants and herbs to protect wounds and absorb exudates. Oil was a key ingredient in these plasters, preventing them from sticking to the wound and slowing down bacterial growth. Now, more than four millennia later, we use more advanced dressing materials, but the goal remains the same: to make wounds heal fast, to avoid infections, and if they should occur, to manage them, especially after surgery.

However, even with great advances in modern medicine, the most common healthcare-associated infection (HAI) remains surgical site infections (SSI). Millions of patients worldwide suffer every year from SSI, which threaten their lives, cause longer hospital stays, higher costs and contribute to the spread of antibiotic resistance 2. Infections of surgical wounds can cause severe damage, hindering wound healing and leading to significant mortality and morbidity. Most SSI are caused by bacteria of the skin flora surrounding the surgical incision such as Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa3. Therefore, post-operative measures such as appropriate dressing of the surgical site are crucial to support healing and prevent SSIs.

When surgeons close surgical incisions, they typically apply a sterile dressing. This material provides a bacterial barrier until physiological re-epithelisation occurs. The wound dressing is usually left in place for 24 to 48 hours unless significant drainage or bleeding from the site occurs4. Overall, this early post-operative phase is critical for wound healing, which is a highly regulated process and requires the close interaction of many factors such as cytokines, growth factors, blood and the extracellular matrix to restore injured skin5.

As soon as a wound is formed, the body reacts. Platelets activate, coagulation starts and a blood clot forms. At the same time, inflammatory mediators are released, blood flow increases and phagocytic white blood cells such as neutrophils and macrophages migrate to the wound site. Those cells are crucial to neutralise bacteria and eliminate necrotic tissue. After the inflammatory phase, the skin starts to rebuild, granulation tissue fills the wound and new blood vessels are formed. It is during this proliferation phase that the wound gradually contracts, and epithelial tissue forms at the edges of the wound. Epithelialisation may be completed in 24 to 48 hours in primary closed wounds or delayed for three to five days in wounds healing by secondary intention. Once the wound is closed, the final maturation phase starts, and collagen is remodelled to give the tissue its tensile strength6. Acute wounds go through these three physiological stages and usually heal within four weeks. But when the healing process does not run smoothly and stalls in one phase, acute wounds progress to a chronic state. Factors as increased levels of inflammatory mediators, infections, biofilm, hypoxia and poor nutrition can negatively influence wound healing and lead to chronic wounds, which can be difficult to treat7. Recognising and treating these factors is key to avoid the disruption of the healing process and the evolution of acute wounds into chronic ones.

Based on the wound type, choosing a surgical site dressing with ideal characteristics for barrier protection is a priority for avoiding SSI. However, there are no standardised recommendations on the best type of post-surgical dressing type8. Today, there are more than 3000 types of dressings available in the market, offering surgeons the possibility of making the best choice of dressing based on the wound type.

Further, modern dressings can do much more than just cover the wound: They can also positively influence the healing process. Therefore, they must meet several requirements9 which include:

Dressings are usually made of synthetic polymers and can be classified in passive, interactive and bioactive products:

Antimicrobial wound dressings can help reduce bacterial colonisation and minimise the incidence of infections11. Growth factors and enzymes are also sometimes included to support repair processes and promote debridement of necrotic tissue, respectively. Mechanical debridement* is also a key component of wound management, as it allows removal of debris, slough, senescent cells and biofilm, preparing the wound bed for reepithelialisation12. In fact, keeping a wound clean and free of debris is crucial to prevent the development of SSI.

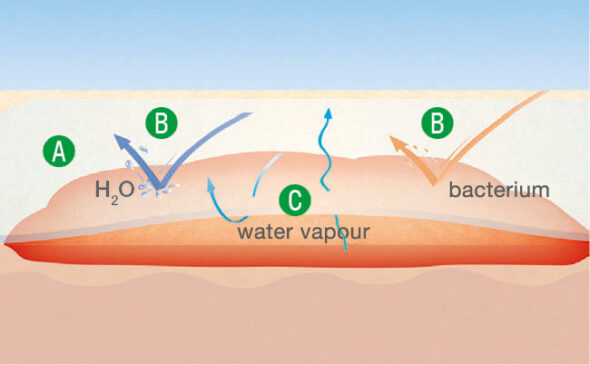

In case of highly exuding wounds, superabsorbent wound dressings represent a very valuable option, as they are able to take up excess amounts of fluid. This is particularly important in the management of chronic wounds13. Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) also represents a popular treatment modality for both acute and chronic wounds. NPWT systems apply subatmospheric pressure to the wound, improving wound healing14.*

When the integrity of the skin barrier is restored, dressings can be removed using clean or aseptic no-touch techniques, depending on the condition of the wound and the patient. During dressing removal, it is mandatory to avoid contact of the wound with infectious material, and hand hygiene guidelines must be followed. It is also important to keep the number of dressing changes as low as possible. Every time a dressing is changed, the wound is exposed to potential pathogens, and the wound healing process slows down. In fact, wound dressings keep the wound at body temperature, ensuring optimal cellular activity for wound healing. After every changing procedure, it takes 3-4 hours for the cells in the wound to resume their tasks15. Reducing the number of dressing changes also results in a possible reduction of skin blistering, periwound skin damage and discomfort for the patient.

During dressing change it is crucial to ease the process for the patients and minimise their discomfort. Explaining the procedure before beginning is as important as involving the patient or family members, if desired. Distraction techniques or the possibility of calling a ’time-out’ during the procedure might also be useful. Effective strategies also include the use of dressings which do not shear the epidermis when removed, the use of warm saline solution to cleanse wounds and the avoidance of cytotoxic solutions which can cause burning16. Using tools which ensure an effective and gentle wound debridement also helps reduce pain for the patient while creating a clean wound bed and preserving intact tissue. It is important to remove slough, devitalised tissue and biofilm during each wound dressing change. Monofilament fibre pads* are very effective tools for mechanical debridement as they are pain- and trauma-free for patients and have therefore a positive influence on compliance17.

A structured approach is key for improving the overall management of surgical wounds. The implementation of standardised protocols and the institution of interdisciplinary teams being responsible for managing a patient’s wound all contribute to reducing the risk of SSI18. While national guidelines might differ in some of their recommendations, they underline the importance of adopting evidence-based protocols and surveillance measures in the fight against infections. Moreover, they underline the importance of enhanced education for healthcare workers, patients and caregivers following WHO’s Five Moments for Hand Hygiene 19. Finally, involving patients in their wound care is an effective way to increase compliance. Patients should be familiar with hygienic measures for infection prevention, such as hand disinfection*.

As one national example, the German Commission for Hospital Hygiene and Infection Prevention (KRINKO) recommends leaving the surgical dressing on the wound until wound healing is completed unless there is evidence of a healing disorder20. In another example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK recommends covering surgical incisions with an appropriate interactive dressing and using aseptic non-touch techniques for changing or removing dressings. Moreover, both the NICE guidelines and the guidelines of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)21 advise against the use of topical antimicrobial agents for surgical wounds that are healing by primary intention22.

Dressing removal, dressing change and wound cleansing are necessary steps that need to be optimised in order to ensure unproblematic wound healing after surgery. The choice of the most effective therapies, good communication among all service providers, patients, and families, sharing of clinical expertise and close follow-up can also avoid potential wound healing problems.

Make sure you receive:

Further information

*Commercial communication